In the footsteps of the Apollo astronauts

Is Iceland like another planet? Many think so – including NASA. In fact, nine of the 12 men who were first to set foot on the Moon in the 1960s and 1970s trained for their mission in Iceland. More recently, scientists have visited the country to test rover technology for the mission to Mars.

By Egill Bjarnason

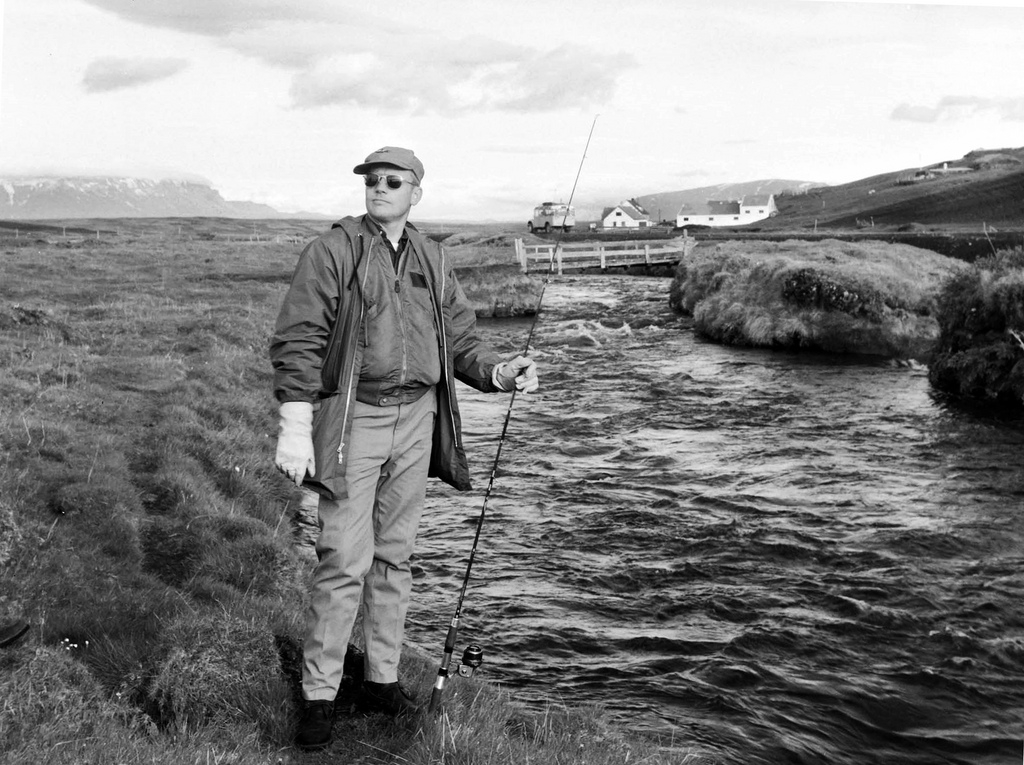

Two years before stepping on the Moon, Neil Armstrong went salmon fishing in North Iceland. A picture of him, standing by the river, is on display at the Exploration Museum in Húsavík, but the image is so small that I didn’t recognize him at first and assumed it was a snapshot of leisure life in the 1960s. Smiling faintly as he holds a fishing rod, the 36-year-old Armstrong could pass for a local—until you consider the baseball cap and fancy aviator shades. And the four layers of clothing.

American legend Neil Armstrong trained for the first Moon expedition in Iceland and unwound by fishing at North Iceland’s best salmon rivers. Photo by Sverrir Pálsson, courtesy of the Exploration Museum.

American legend Neil Armstrong trained for the first Moon expedition in Iceland and unwound by fishing at North Iceland’s best salmon rivers. Photo by Sverrir Pálsson, courtesy of the Exploration Museum.

Other prospective spacemen were in the country at the same time too, living in NASA training camps in Iceland’s interior. It was summer, and the constant daylight obscured their ultimate destination. In the middle of Iceland’s Highlands, NASA had found a parallel lunar landscape: no vegetation, no life, no colors, no landmarks.

“They were pilots by trade, not geologists,” says Leonardo Piccione, Italian author of Il libro dei vulcani d’Islanda (“The book of Icelandic volcanoes”), which has a chapter devoted to the much forgotten history of Iceland’s role in the Moon landing. “So the Iceland curriculum started with elementary definitions, explaining the basalt rocks and magma.”

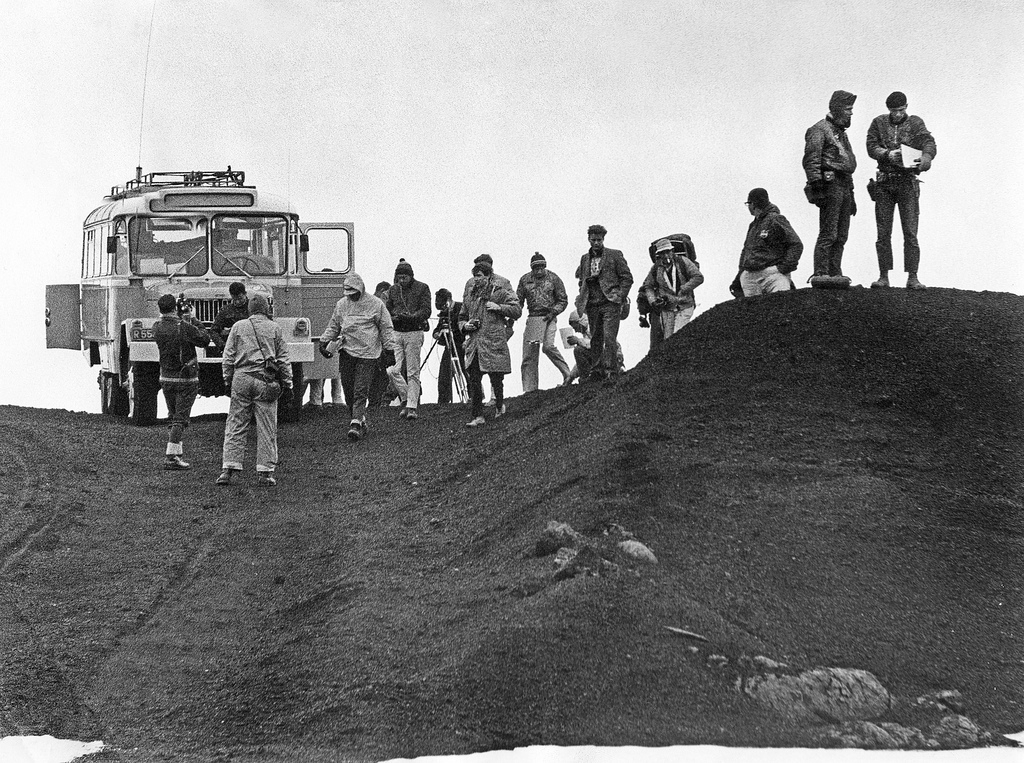

Nine of the 12 men who set foot on the Moon between 1969 and 1972 first came to Iceland as part of the Apollo geology field exercises to study the country’s geology, the idea being that it would help them understand the Moon’s geology when they visited. The exercises included the “Moon game”: The astronauts would pretend to be on the Moon and attempt to complete the most important field observations, such as collecting samples.

During the Apollo geology field exercises in Iceland. The region where the astronauts trained became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019. Photo by Kári Jónasson, courtesy of the Exploration Museum.

During the Apollo geology field exercises in Iceland. The region where the astronauts trained became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019. Photo by Kári Jónasson, courtesy of the Exploration Museum.

Lunar-like soccer field

The area where the astronauts trained is a boundless Icelandic desert, shaped by volcanic eruptions and covered in different shades of lava. Named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in July 2019 as part of Vatnajökull National Park, the Askja region is essentially a natural gravel field. The would-be astronauts took advantage of it by splitting into teams and playing soccer to unwind after training days, using rocks to mark the goalposts.

The astronauts traveled on Land Rovers, much like today’s travelers—the roads haven’t improved much. The most common tour to Askja is via Herðubreiðalindir on Route F88, east of Lake Mývatn. Some three hours on the rocky road, crossing two rivers, will eventually lead to a middle-of-nowhere campsite at the Drekagil canyon. Three cabins line the canyon mouth like the mansions of a James Bond villain. The newest wooden house is from the Vatnajökull National Park, with a very casual information desk open whenever the ranger is not out and about. “Some people think we’re a coffee shop or a restaurant. That would be a tough business up here,” says park ranger Sigurður Erlingsson, who’s stationed at the hut every summer.

Moon walking in Nautagil

When I visit on a sunny day in July, the Drekagil base camp has steady stream of visitors. One German couple is drying bright beach towels at the campsite. They’ve just completed a hike to Víti, a crater lake fed by geothermal hot springs. Some 3,300 ft (1,000 m) above sea level, the stunning crater offers a warm but muddy bath. Just next to Víti is the Askja caldera, the largest in the volcanic belt, stretching a total of 112 miles (180 km) north of the Vatnajökull glacier. The last eruption was in 2014, lasting six months and producing a lava field the size of Manhattan.

But I was headed away from the scenic route to a neighboring canyon, one that was without a name when the astronauts visited half a century earlier. It is now called Nautagil, a play on words and language honoring the history: naut—as in “astronaut”— means “bull” in Icelandic. Sigurður, the park ranger, joins me on this special “Moon walk” through the canyon. We walk up a steep slope for a better view over the area. “I like to think these tracks are from the NASA years,” he says, pointing to a faint but broad line in the landscape. It’s possible: The cold and desolate landscape takes incredibly long to heal, explaining the hefty fines for any off-road driving. I try to locate some of the photographs from the time and wonder why this site doesn’t see more visitors. Its significance to the actual Moon landing is maybe small, yet it’s a rare opportunity to step back in time, like holding an object from the mission.

From the Moon to Mars

On July 24, 1969, Apollo 11 landed back on Earth with a geological sample—a slice of the Moon. The resemblance to Iceland was superficial. NASA had originally drawn the parallel from images taken by a space probe orbiting Earth’s satellite years before; the lunar Highlands (seen from afar as the lighter surface regions) looked like Iceland’s desolate interior. For decades to follow, Iceland was off the map for NASA until scientists began planning a new mission. To the fourth planet from the Sun: Mars.

This past summer (2019), scientists from NASA spent two weeks in the Highlands testing the prototype of a self-driving rover truck set to explore Mars in 2021. Another team is expected to follow, but for the underground. Iceland and Mars, beyond similarities in rocky terrain, both have lava tubes, caves formed when the lava moves beneath the hardened surface. Iceland’s longest caves are formed this way and can be easily accessed from the ground. Scientists hope lava tubes can serve as shelters for equipment (or humans?) on future Mars missions.

The Hverfjall crater east of Lake Mývatn. Photo by Robin Wittwer.

The Hverfjall crater east of Lake Mývatn. Photo by Robin Wittwer.

Exploring the human side

The Moon landing has a human side even more powerful than the scientific details. The ambitious Exploration Museum, located on the main street in Húsavík in North Iceland, celebrates Iceland’s contribution to the Moon landing in a gallery space also showcasing early Viking explorations, Polar explorers, aviators and seafarers —people who set out into the unknown to obtain new knowledge.

The museum’s founder Örlygur Hnefill Örlygsson, moonlighting as a filmmaker, sets out to explore the meaning of the Moon landing in the new documentary feature Cosmic Birth. He interviews many of the spacemen who visited Iceland at the time and even revisits the area with some of the American legends. “We went to the Moon and discovered the Earth,” Örlygur cites when introducing William Anders, who took Earthrise, the famous photograph of the Earth from the lunar orbit. Anders, who used a color-film Hasselblad camera, knew Iceland from the time he was stationed at the US Navy base in Keflavík some years earlier. He recalled the fun times trekking and exploring the Icelandic wilderness. One of his pals, an adventurous type from Ohio, asked if the area where they were training had any good rivers for fishing. In fact, it had some of the best in the country, and the two of them arranged to borrow some rods, as Anders remembers: “Armstrong and I had a lot of fun fishing.”

This article first appeared in the Icelandair Stopover magazine, fall 2019.